Preface: I think it’s great that Marty Friedman is so enthusiastic about Japanese pop music. However, for someone who has apparently been living or traveling to Japan for so long and speaks fluent Japanese, it is astonishing how little he understands the full scope of it. And as a musician (former member of Megadeth, current guitar virtuoso), writer, and speaker, it’s even more astonishing how his lecture “What is J-POP? ~Exposing the Myth of Japanese Music Phenomenon” is partly a failure of articulation. Friedman has ideas, they just get tangled and sprout half-formed. His tone borders on less-than-conversational, barely scratching the surface of popular Japanese music, while exposing his biases and the kind of thinking that makes one believe everything off one’s radar doesn’t exist at all. So basically, it might sound like I’m tearing this to pieces, and I guess I am, but since Friedman takes the time to apologize for his tastes several times during the lecture, I guess I can take the time to do it at least once: this lecture just wasn’t my thing. Sorry.

“And the main reason why I want to do this is because now is the time that Japan and its music scene is going to begin to be well-known outside of Japan. I think it’s really beginning now and […] I believe Japan’s music is the future.”

Japanese popular music has pretty much been around as long as its American counterpart, as Friedman himself takes pains to discuss. However, why Friedman thinks that now is the time that Japanese pop will “explode” is unclear. If any country can be predicted to hold the future of the world’s music right now (and I hate that I keep returning here, but it’s inevitable), that would be South Korea. Besides the fact that South Korea is motivated by economic factors (Japanese musicians don’t necessarily need foreign sales to thrive — plus, as mentioned in the lecture, kids will buy three or four copies of a single to collect all the singles or get the trading cards, while the South Korean music market pales in comparison), it also has a brilliant PR campaign the likes of which Japan has yet to utilize. While Japan patrols YouTube like a nark, pulling uploads and refusing to post full-length PVs, South Korea has successfully exploited social media to create viral videos and establish a brand. Many artists are already mingling or collaborating with foreign musicians, itself an easy transition when K-pop sounds like the smartest, hippest pop music upgraded to 11. And unlike Friedman’s lumping of J-pop into one large genre as if AKB48, X Japan (though he does use the term “visual-kei” here — more on that later), and Perfume all have the same sound, K-pop does have the luxury of that label: contemporary Korean pop music and groups are certainly easier to lump together than Japanese pop will ever be.

Later in the lecture, Friedman takes this further by positing that the future is a lot closer than we might anticipate: “all the stuff I introduced to you from Japan is going to make it outside of Japan, and soon. I’m surprised it hasn’t happened already. I’m talking this year, or next year something is going to explode because this stuff is too good.” It takes a lot more than a few punk rock secretaries to make a movement, and even with South Korea’s expert marketing campaign, it’s already taken several years of very determined, very aggressive action to gain the sliver of media attention that K-pop has gotten. Japan is already set for failure as there aren’t many record labels and entertainment agencies that care that much about making a name outside Japan. Furthermore, to expect groups like, say, a Johnny & Associates group or the AKB/NMB etc. trend to gain traction in the West without a grasp of context and culture, is unlikely. Where it’s already associated with anime tie-ins and appearances at comic cons, it has already failed miserably by equating music culture with otaku culture, as if the two are never one without the other. It will take much longer to reverse what has already become the mainstream idea of what “Japan” and “Japanese culture” denotes to the average American citizen because of a reluctance to change it and refusal to be militant in doing so. When Friedman says things like “not only because it’s so whacked and so freaking crazy but also so cool, so colorful and so happy,” he’s really not doing Japan any favors, and certainly not changing anyone’s mind regarding stereotypes. Furthermore, in reference to his later championing of visual-kei…it’s been around for decades. Which is a long time. Again, I’m happy he’s so enthusiastic about this, but it’s not going to “explode” in 2012. It’s had the chance to explode for many, many years. And it hasn’t.

After playing Ikimonogakari’s “Arigatou,” Friedman says, “It’s just a gorgeous melody and it’s kind of sad in a different way than “sad” music is in Western music. When I think of sad music in Western music I would think of something like Adele or something like that.” I think the word he’s looking for is “nostalgia” (and possibly the overall theory of musical authenticity). Why the concept of nostalgia would not come to somebody who has apparently been listening to Japanese pop music for so long is strange, as it is an integral part of what constitutes Japanese pop culture. When he says this sound evolved from kayoukyoku music from “maybe 20-30-40 years ago” — well, which is it? Because that’s a huge chunk of time to be playing with, and Japanese pop music from the 80s, 70s, and 60s, all sounds extremely different and could be as easily lumped together as the contemporary styles are today: for Friedman, Japanese pop is no more dynamic than someone’s idea of Japanese culture consisting of geishas, rock gardens, and kabuki masks.

His giant theory of a unified J-pop extends into technical arenas as well, for example when he talks about Perfume’s “POLYRHYTHM.” “This is another thing about Japanese music is they can accept deep technical concepts within the context of ultra pop music.” “POLYRHYTHM” does indeed have some crazy-awesome time signatures going on, and it is arguably one of my favorite pop songs of all time, but using this song as an example of Perfume’s overall musical style is naive, as is calling Perfume’s music “the music of the future.” Technically, this is already the music of the past, as “POLYRHYTHM” was released five years ago. Furthermore, the group is still best known for their single “CHOCOLATE DISCO” which was released in 2007. Producer Yasutaka Nakata has since gone on to write and produce hundreds of songs with several artists, all with a similar, signature sound. That doesn’t diminish how great the music is, but it certainly no longer makes it worthy of being “the music of the future.” Sure, he’s spot on when he says “the main thing about this unit [Perfume] is the producer is a genius.” It’s probably the only 100% accurate statement in this piece. Unfortunately, he then goes on to call the founder of AKB48 a genius, which kind of takes away some of Nakata’s glory, and then basically calls the entire Japanese pop enterprise a genius, so the word loses its meaning and makes J-pop seem infallible, which is the least kind of logical argument someone can make for anything. Nothing is perfect and calling J-pop flawless takes away part of what it makes it so fun to listen to and discuss.

Friedman goes on to make an inadvertent testament to how Japanese pop really works when he moves on to Mr. Children, confirming that it’s “not going to sound like anything new, they’ve been around for at least 10-15 years. But every album is consistently a huge hit due to the quality of their song writing and performance.” Rather, I think Mr. Children’s popularity is due largely to the idea of loyalty that fans have to bands and artists that allow groups like Mr. Children and B’z to continue releasing music simply because there is a ready made audience that will buy the new single and the sort of respect legendary artists accumulate with time. But in the grand scheme of Japanese music, popular or otherwise, I would argue that Mr. Children and B’z have hit their stride years ago and remain faintly relevant, a perennial fixture on the landscape of Japanese pop.

“People in France might know X-Japan, because X-Japan is successful here and they toured outside of Japan, just like Dir en Grey did. But in Japan X-Japan are the ancestors, they brought it to the mainstream first. […] They are the Godfathers. They started it, they set the pattern of it. And now its 2012 and finally its making its way out of Japan.”

Is it though? And if X Japan are the ancestors, why are we still talking about them? Has visual-kei evolved so little that X Japan, who were popular twenty years ago, are still the most relevant example Friedman can offer? He then continues to namedrop more relics and claims visual kei is going through a “big boom” right now. But visual-kei never really went away; it’s not really experiencing a big boom, so much as it’s riding a pretty stable wave. Second of all, if it’s going through a big boom, where are all the great bands that haven’t been around for a decade? MUCC, Dir en grey, L’arc~en~Ciel…these are all bands I remember from when I was getting into Japanese rock fourteen years ago who had already been around for a while. Instead of trying to show how Japanese pop music is a flourishing, diverse enterprise, he’s really just showing how stagnant it’s gotten.

It’s a shame that the questions he received during panel were so thorough, because I don’t think Friedman takes the time to really consider them. For example, the first question asks how the Japanese can avoid falling into the traps of prejudice when trying to export their sound to the West. After talking around the issue, Friedman says, “I think a lot of it has to do with luck, a lot of it has to do with timing, the right person and the right song, I don’t think it’s something you can plan” (this probably coincides with his constant equating of “magic” with Japanese pop music, as if it sprouts from a land of mythical creatures). This doesn’t make any sense: it sounds exactly like the sort of approach that has already been taken and has failed miserably for it. He might as well claim he’s definitely going to win the lottery next year without having to buy a ticket. How much of South Korean pop music’s relative success has been due to “luck” and being in the “right place at the right time”? None of it. South Korean entertainment companies have used smart, consistent advertising techniques, employed expert use of social networks, and have probably had hundreds of meetings where strategies and goals have been calculated and re-calculated. This is not an endeavor that takes luck. It does not take the defeated strategy that you “can’t plan for something outside of your country.” His example is Yuki Saori, a young woman whose song was stumbled upon in a record store and led to her being invited to sing in London. That’s definitely a great way to get noticed outside Japan: hope your record is found in a 50 cent used bin somewhere and hope for the best!

Without offering any practical advice for how Japanese pop music will “explode” in the next year or two, Freidman comes off as a very enthusiastic, very sincere, fan whose obsession has blocked his ability to think rationally. Regarding the language barrier, he says Adele is difficult for Japanese listeners to get into because “they would have to really study the lyrics and have personal relationships that are similar to hers and that is hard because it’s in a different culture.” So how he thinks Japanese pop music can make that incredible leap is uncertain, especially when he later claims that the Japanese do not need to sing songs in English and should stick to their native language. Apparently, the Japanese can’t “get” us, but Americans will be able to “get” them right away.

And also: There is a (possibly unintended, but nonetheless, noteworthy for being so) fixation on female musicians, if not a simply patronizing tone toward females that escalates throughout the duration, none of which has a male counterpart anywhere in the lecture.

- The fans of visual-kei are “about 90% females. Go figure, females listening to this kind of music.” Women can like metal, too. Go figure! Sometimes they even use the Internet. Go figure! (By the way, he concludes that girls just like the visual aspect, it’s guys who like the music.)

- American music is “very kind of dull, it’s like subdued. It’s kind of like girls with candles in their room and incense and pillows and it’s not insane.”

- SCANDAL, a four-member rock group whose schtick is wearing school uniforms would be huge in America because “you never think of cute girls playing rock.”

- Nirvana was able to see the brilliance of Shonen Knife because “these were three tiny Japanese secretaries playing punk rock.”

Friedman likes cute girls, we get it. That’s not a bad thing. But the fixation on quiet girls with stereotypical quiet professions or lifestyles stops being quirky and starts becoming really condescending. During the panel, he answers a question saying that “in America the image of Japanese or Asian person is smart or brainy. They’re doing the best in school and they have a very good image.” This remark is made as if the image is inevitable and is the reason he “can’t see any Asian girl singer being like Beyonce or something like that, I just don’t see it happening.” Friedman has clearly never met Namie Amuro or Koda Kumi, two of the most popular female singers in Japan, whose attitude and image are nothing like AKB48, and, while probably not too much like Beyonce either, are certainly not what Friedman considers the ideal J-pop spokesgirl, the kind in SCANDAL or Perfume that he believes should be perpetuated in the West without necessarily introducing their dynamic, diverse equals.

By distilling Japanese pop music to the lowest common denominator in every single way, be it in genre, style, technique, or gender, Friedman actually perpetuates the real myth of Japanese pop music — that it is as stereotypical, static, and wacky as an average American might imagine. What he is “exposing” in this lecture is unclear and the myth actually takes on epic proportions as it continues (although I think his “myth” is that Japan doesn’t have it’s own music, let alone in such abundance, but I don’t think the existence of Japanese pop music is a myth anymore, so much as a fact people choose to ignore). Again, I love his enthusiasm for Japanese pop music and his vision of seeing it get more global attention, but these are exactly the type of incomplete ideas you don’t want presented in front of a large group of people meant to build a foundation for their ideas of Japanese pop music. I don’t know what Friedman’s actual knowledge of the history of Japanese pop music is, nor what his knowledge of its contemporary pop music is, but from this lecture, he comes off as the type of guy who recently discovered an AKB48 song, did a little bit of research on Wikipedia or the Oricon charts, casually browsed a major record store for something similar, and tried to find everything in the world that supported his theory that it’s the only type of music Japan does (or should do). Of course, this involves ignoring the multitude of Japanese pop artists and groups, the array of styles and techniques, the dissatisfaction many Japanese have with their own popular music, the very large indie scene, and the struggle many Japanese and Asians face regarding their ethnicity and/or gender. And that is a big deal.

Even more than Japonism, was the group’s follow-up single “Fukkatsu LOVE,” which already promised to be amazing upon the announcement of its producer Tatsuro Yamashita’s involvement. Yamashita was a beast in the 80’s, the type of king who lorded over his tiny City Pop kingdom as a benevolent, jovial ruler who took the time to nurture his craft and give his songs the care and attention they deserved. Like the best pop music, his songs are deceiving. They’re simple: simple bars, simple melodies. The lyrics? We’re talking Japanese 101, the stuff you can translate after a few days of relaxing with the Oricon Top 10 and a couple lessons of survival phrases. So then why are they so addictive? How do they manage to so perfectly encapsulate their time and place in the canon? How do you resist snapping your fingers and tapping your toes when something like “

Even more than Japonism, was the group’s follow-up single “Fukkatsu LOVE,” which already promised to be amazing upon the announcement of its producer Tatsuro Yamashita’s involvement. Yamashita was a beast in the 80’s, the type of king who lorded over his tiny City Pop kingdom as a benevolent, jovial ruler who took the time to nurture his craft and give his songs the care and attention they deserved. Like the best pop music, his songs are deceiving. They’re simple: simple bars, simple melodies. The lyrics? We’re talking Japanese 101, the stuff you can translate after a few days of relaxing with the Oricon Top 10 and a couple lessons of survival phrases. So then why are they so addictive? How do they manage to so perfectly encapsulate their time and place in the canon? How do you resist snapping your fingers and tapping your toes when something like “ We can argue and complain about how the past decade or so has seen a swift decline in the quality and variety of music that used to define modern Japanese pop music, largely due to groups just like Arashi and their female-idol counterparts in Akimoto-driven AKB-sister groups, even as we praise them for contributing to some of the most fun singles of the year (we all know “LOVE TRIP” was pretty fun). Pop music is nothing if not the definition of fast-paced change, with songs jumping in and out of relevance before we’ve even finished downloading them. Because of this, it’s sometimes easy to dismiss every big K-pop single as just the next song to tide you over until tomorrow’s rookie group debuts, or SM Entertainment unleashes SHINee’s tenth comeback. In Love for Sale: Pop Music in America, David Hajdu recalls how

We can argue and complain about how the past decade or so has seen a swift decline in the quality and variety of music that used to define modern Japanese pop music, largely due to groups just like Arashi and their female-idol counterparts in Akimoto-driven AKB-sister groups, even as we praise them for contributing to some of the most fun singles of the year (we all know “LOVE TRIP” was pretty fun). Pop music is nothing if not the definition of fast-paced change, with songs jumping in and out of relevance before we’ve even finished downloading them. Because of this, it’s sometimes easy to dismiss every big K-pop single as just the next song to tide you over until tomorrow’s rookie group debuts, or SM Entertainment unleashes SHINee’s tenth comeback. In Love for Sale: Pop Music in America, David Hajdu recalls how How much of Arashi’s popularity is real versus the careful manufacture of the company’s almost dynastic, but slowly ebbing monopoly over media? (Think about their resistance to the Internet and its inherent power to equalize and neutralize and divide pop culture, while providing alternatives and putting the nature of its dissemination in the hands of fans and fandoms and ah, yes, I see your point Japanese entertainment companies, but the capitulation is inevitable and you’d be wise to find ways to make it work rather than sulk and refuse to find ways to make it work). I’m not talking about the members’ inherent talent, charisma, and good looks, which they have all so obviously spent years and millions making sure they have or appear to have. But what other boy band had Tatsuro Yamashita? SMAP did have Yasutaka Nakata, once, long ago now, but it was clearly one of his chopping-block singles. It might seem sinister or oddly disconcerting that pop greats like Yamashita would “deign” to work with just another idol group, but on the contrary, history has shown us that only the greats had the privilege of doing so. Perhaps we’re living in an age where the well-respected have decided to join ’em, rather than beat ’em, but maybe there’s something worth examining here. Let’s put it another way: will it be AKB48 or Perfume or Arashi performing at the 2020 Olympics?

How much of Arashi’s popularity is real versus the careful manufacture of the company’s almost dynastic, but slowly ebbing monopoly over media? (Think about their resistance to the Internet and its inherent power to equalize and neutralize and divide pop culture, while providing alternatives and putting the nature of its dissemination in the hands of fans and fandoms and ah, yes, I see your point Japanese entertainment companies, but the capitulation is inevitable and you’d be wise to find ways to make it work rather than sulk and refuse to find ways to make it work). I’m not talking about the members’ inherent talent, charisma, and good looks, which they have all so obviously spent years and millions making sure they have or appear to have. But what other boy band had Tatsuro Yamashita? SMAP did have Yasutaka Nakata, once, long ago now, but it was clearly one of his chopping-block singles. It might seem sinister or oddly disconcerting that pop greats like Yamashita would “deign” to work with just another idol group, but on the contrary, history has shown us that only the greats had the privilege of doing so. Perhaps we’re living in an age where the well-respected have decided to join ’em, rather than beat ’em, but maybe there’s something worth examining here. Let’s put it another way: will it be AKB48 or Perfume or Arashi performing at the 2020 Olympics?

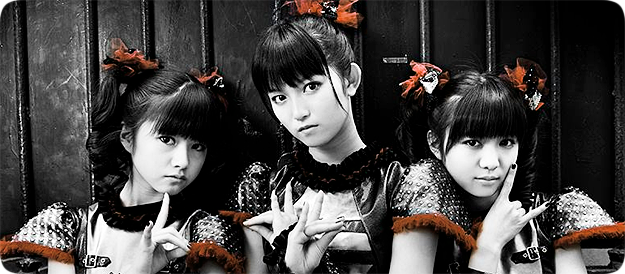

That last point is a stretch, and none of the artists briefly profiled could be considered to have gained “mainstream” success (Rappers Novelist and Kodak Black, piano prodigy Joey Alexander, popster Låpsley, etc.), but the New Yorker wouldn’t be the New Yorker if it didn’t purport to being on the absolute up-and-up. As in TIME‘s special Fall 2001 issue, which featured Hikaru Utada, (notably, she was working on her American debut with Foxy Brown and the Neptunes and planning to retire very young, around 28, probably to become a neuroscientist), articles like these tend to be peak Western exposure for said artists, rather than the beginning of a phenomenon, though BABYMETAL does get relatively considerable space. Writes Trammell,

That last point is a stretch, and none of the artists briefly profiled could be considered to have gained “mainstream” success (Rappers Novelist and Kodak Black, piano prodigy Joey Alexander, popster Låpsley, etc.), but the New Yorker wouldn’t be the New Yorker if it didn’t purport to being on the absolute up-and-up. As in TIME‘s special Fall 2001 issue, which featured Hikaru Utada, (notably, she was working on her American debut with Foxy Brown and the Neptunes and planning to retire very young, around 28, probably to become a neuroscientist), articles like these tend to be peak Western exposure for said artists, rather than the beginning of a phenomenon, though BABYMETAL does get relatively considerable space. Writes Trammell, In many ways this is a sign of the outrageous gender binaries that comprise the marketing and distribution of Japanese idols; for purposes of the music itself, it also reinforces the notion that genres that comprise huge male audiences (hard rock, metal) can be deemed authentic and worthy of critical attention, while those that women enjoy are considered fluff that no one would ever take seriously. Under that idea, it’s hardly surprising that a group like BABYMETAL could make it in the circles of certain American subcultures, and less so that articles in the Western media feel the need to justify their interest in the group by constantly reminding readers that their material was written by veterans of the metal genre (Nobuki Narasaki, Herman Li, Sam Totman, Takeshi Ueda, etc.), or that the girls themselves are influenced, or appreciated by,

In many ways this is a sign of the outrageous gender binaries that comprise the marketing and distribution of Japanese idols; for purposes of the music itself, it also reinforces the notion that genres that comprise huge male audiences (hard rock, metal) can be deemed authentic and worthy of critical attention, while those that women enjoy are considered fluff that no one would ever take seriously. Under that idea, it’s hardly surprising that a group like BABYMETAL could make it in the circles of certain American subcultures, and less so that articles in the Western media feel the need to justify their interest in the group by constantly reminding readers that their material was written by veterans of the metal genre (Nobuki Narasaki, Herman Li, Sam Totman, Takeshi Ueda, etc.), or that the girls themselves are influenced, or appreciated by,  While Marty Friedman believed that Japanese pop music would only reach an audience outside Japan “with luck” and “timing,” and other factors that couldn’t be planned, BABYMETAL, has been a slow, methodical climb to relevance, not least of which included shows in Paris, New York, and the UK, and opening for Lady Gaga’s ArtRave: The Artpop Ball tour starting back in 2014.

While Marty Friedman believed that Japanese pop music would only reach an audience outside Japan “with luck” and “timing,” and other factors that couldn’t be planned, BABYMETAL, has been a slow, methodical climb to relevance, not least of which included shows in Paris, New York, and the UK, and opening for Lady Gaga’s ArtRave: The Artpop Ball tour starting back in 2014.  That being said, in rare cases the music can transcend context, as BABYMETAL’s fantastic new album, METAL RESISTANCE, does. There are some truly epic and astounding risks the album takes and pulls off, particularly with lead tracks “

That being said, in rare cases the music can transcend context, as BABYMETAL’s fantastic new album, METAL RESISTANCE, does. There are some truly epic and astounding risks the album takes and pulls off, particularly with lead tracks “