Some artists have been around for so long that it’s easy to take them for granted, their existence a ubiquitous modern convenience, like airplanes or light bulbs. And their origin stories seem so irrelevant, that they hardly seem worth questioning; like Moses floating on a riverbed, their delivery seems inevitable, a gift from the music gods that simply emerged one day among the cattails. Since they’ve always been around, it feels like they always will, and so it becomes easy to let interesting work slip through the cracks. Takanori Nishikawa can seem like that sometimes, each new release like a routine dental check-up — ah yes, it’s that time again — but in reality, he has done a lot of good, ground-breaking work, constantly reinventing his look (if maybe not his sound) with each release, and with some side-projects that still seem a tad ahead of their time, just a bit like they got swept under the rug of a household name whom by that point, was dismissed as a bit of a joke, and a little bit of a has-been.

In Taylor Swift’s Netflix documentary, Miss Americana, the singer laments how often women must reinvent themselves to stay relevant and interesting, especially as they age and are sentenced to “an elephant graveyard by the time they’re 35.” One would imagine Takanori Nishikawa, born in a country where the turnover rate for idols can cause vertigo, was introduced to the concept of reinvention at a young age and instead found his raison d’etre, a kind of freedom that he saw less as chains and more as the liberation to experiment and explore, a way to keep things fresh when they seemed stagnant. The singer has been evolving since he found a receptive audience, almost with each single, and he certainly didn’t limit it to the people with whom he worked.

In the beginning

Takanori Nishikawa began his career in the early 1990s in a visual-kei band, before getting his first big break when he teamed up with Asakura Daisuke. This fortuitous meeting led to the formation of T.M.Revolution, short for Takanori Makes Revolution. The purpose of the name was to include all of the musical creators who contributed to make Nishikawa one of the most successful male solo artists of the late 90s (and we know how scarce and coveted those are today). He scored his first #1 album on the Oricon with 1998’s triple joker, and celebrated in style by releasing one of the most fantastically trippy J-pop music videos of all time for his next single “HOT LIMIT,” in an outfit that has become so iconic, it now has its own homages and gross figurines, though it has also made him the tail-end of many jokes (which he luckily seems to take in good-humored stride). Till then, Nishikawa was increasingly, and understandably, relegated to the otaku-zone: occasionally, his work was peppered with slightly darker content, like “Slight faith,” and “AQUALOVERS ~ DEEP into the night,” but mostly his songs took on the often highly dramatic air of shounen animation, an amalgamation of the genre’s staple sounds – bright, speedy rock music with lyrical content that reflected the target audience: staying strong, moving forward, never giving up, and tapping into your inner power.

Takanori Nishikawa began his career in the early 1990s in a visual-kei band, before getting his first big break when he teamed up with Asakura Daisuke. This fortuitous meeting led to the formation of T.M.Revolution, short for Takanori Makes Revolution. The purpose of the name was to include all of the musical creators who contributed to make Nishikawa one of the most successful male solo artists of the late 90s (and we know how scarce and coveted those are today). He scored his first #1 album on the Oricon with 1998’s triple joker, and celebrated in style by releasing one of the most fantastically trippy J-pop music videos of all time for his next single “HOT LIMIT,” in an outfit that has become so iconic, it now has its own homages and gross figurines, though it has also made him the tail-end of many jokes (which he luckily seems to take in good-humored stride). Till then, Nishikawa was increasingly, and understandably, relegated to the otaku-zone: occasionally, his work was peppered with slightly darker content, like “Slight faith,” and “AQUALOVERS ~ DEEP into the night,” but mostly his songs took on the often highly dramatic air of shounen animation, an amalgamation of the genre’s staple sounds – bright, speedy rock music with lyrical content that reflected the target audience: staying strong, moving forward, never giving up, and tapping into your inner power.

And as the music became more dramatic and anime-adjacent, his look became accordingly more cartoonish. Quasi-cos-play began to feature heavily into the way his work was marketed, from the jungle-animal-aesthetic of “WILD RUSH” (used to promote Teressa Jungle Jungle hair-care products), to “Burnin’ X’mas,” where he dressed as a kind of Dollar Tree-fashion Father Christmas for the jacket photo and promo appearances. The cover of his 1999 album, the force, featured the singer in two opposing looks — lounging in a hyper-flat fantasy Eden, abundant with fruit and birdsong, and a sly, skull-bearing demon. This very Shelley Duval’s Faerie Tale Theatre-production was just a taste of the visual components Nishikawa envisioned for himself and his music. But the singer seemed bored, and when pop stars get stuck in a rut, there’s one surefire way to spice things up.

It was around this time that he first put T.M.Revolution on hold to once again team up with old pal Asakura Daisuke for the end of genesis T.M.R.evolution turbo type D, or TMR-e, project. A one-off, this more moody, atmospheric music didn’t hit it off as much the duo hoped, and they soon parted ways. The diversion put a bit of a stumble in Nishikawa’s step, and he took a few years to regain his footing, releasing mostly bland, safe rock music after 2000’s incredible opus progress. As he rooted around for traction back in the world of anime, which had continued to explode with new talent like Nami Tamaki and Nana Mizuki, even as his peers began falling to the wayside (shout out to anyone who remembers and appreciates Two-Mix), he tried on a few new personae: that of stateside crossover with 2003’s coordinate, television emcee on beloved music show Pop Jam (RIP), and finally, nostalgia-bait with a slew of best-ofs and self-cover albums.

abingdon boys school

But one of his greatest creative outlets was the short-lived side-project abingdon boys school. The band, which consisted of T.M.Revolution members SUNAO (guitar), Shibasaki Hiroshi (guitar and principal composing), and Kishi Toshiyuki (synths, programming, composing), formed in 2005, and named themselves after the real-life Abingdon School located in Oxfordshire, England. Of course, Nishikawa never leaves things at a 5 when he can take it to 10, so the group went all in, dressing up in the uniforms of boys decades younger (the members were all in their mid-30s when the group formed), and posing next to vintage sports equipment and British automobiles in press material. This would all be a kind of cute lark if the music wasn’t a jump in quality from anything T.M.R. had been coming up with in the last few years. Not only that, but the cos-play angle was a bit novel for an all-male band[1]: with the startling number of J-pop girl groups marketed wearing school uniforms and other straight-male fantasy costumes (French maids, flight attendants), it could leave audiences wondering where the male equivalents were. Nishikawa seemed destined to fill this gap with what was now a long history of subversive, highly-stylized stage looks. Aside from the requisite make-up-heavy groundwork laid by visual-kei bands and the like, who pulled from vintage gothic-horror fashion movements that reflected the counter-cultural ethos and heavy music more than their implied servility to an audience (I would exclude a handful of artists, Gackt for example, who were also genuinely radical), there were few all-male groups that reflected the sartorial diversity of options for male performers, particularly in relation to their audience.

But one of his greatest creative outlets was the short-lived side-project abingdon boys school. The band, which consisted of T.M.Revolution members SUNAO (guitar), Shibasaki Hiroshi (guitar and principal composing), and Kishi Toshiyuki (synths, programming, composing), formed in 2005, and named themselves after the real-life Abingdon School located in Oxfordshire, England. Of course, Nishikawa never leaves things at a 5 when he can take it to 10, so the group went all in, dressing up in the uniforms of boys decades younger (the members were all in their mid-30s when the group formed), and posing next to vintage sports equipment and British automobiles in press material. This would all be a kind of cute lark if the music wasn’t a jump in quality from anything T.M.R. had been coming up with in the last few years. Not only that, but the cos-play angle was a bit novel for an all-male band[1]: with the startling number of J-pop girl groups marketed wearing school uniforms and other straight-male fantasy costumes (French maids, flight attendants), it could leave audiences wondering where the male equivalents were. Nishikawa seemed destined to fill this gap with what was now a long history of subversive, highly-stylized stage looks. Aside from the requisite make-up-heavy groundwork laid by visual-kei bands and the like, who pulled from vintage gothic-horror fashion movements that reflected the counter-cultural ethos and heavy music more than their implied servility to an audience (I would exclude a handful of artists, Gackt for example, who were also genuinely radical), there were few all-male groups that reflected the sartorial diversity of options for male performers, particularly in relation to their audience.

The only difference here, was that, being all-male, abingdon boys school, despite, and let me repeat this, being 30-year-olds wearing school uniforms, was never sexualized the way that female groups like AKB48 were, for which only one reason is that this look was chosen, rather than necessarily thrust upon them by the demands of a male-consumer driven market — it was an option, not necessarily a requisite, like their counterparts. Nishikawa was simply lucky in this sense — as long as he continued to play the game, he got away with it, without having his vision and music questioned or devalued by what he was wearing. Which is important when you think about how great abingdon’s music was.

Unlike the poppier, kid-friendly rock of Nishikawa’s early work, their music was louder, heavier, and darker, though still buffeted by Nishikawa’s signature resounding vibrato. Many of the songs were about having been treated badly by exes, or being unable to move on from broken relationships. They expressed angst, frustration, and even anger, all soundtracked to a propulsive wall of guitar feedback that only got more interesting as the singles piled up. abingdon boys school released their first self-titled album in 2007, drawing largely from Western hard rock and nu metal influences filtered through the inescapable J-rock major-chord cadence of bands like GLAY and L’arc~en~Ciel. Unlike many of T.M.R.’s songs, these were riff-heavy, and less concerned with adding a touch of symphonic grandeur, though pinches of those occasionally peeped out from corners like vigilant reminders of their origins.

The band released their follow-up album in 2010, their last, and though it did as well as their debut, they soon stopped releasing original material, only reuniting as a live band to play local rock festivals. Indeed, they just played a casual set at INAZUMA ROCK FES. in 2019, for which you’ll notice one glaring omission right off the bat: the absence of their trademark school uniforms. Perhaps it’s their age, or time itself, or the atmosphere of the festival, but it’s one gimmick that seems to have fallen to the wayside, a performance no longer required, stuck in the photo studios that forever captured and left us with one brief moment of an impeccable, Japanese rock band clothed in the gimmicky uniforms of those far younger than they were. It’s an interesting rewind from a man whose whole career is practically based on playing a part. But as they are now, they can be agenda-less, T-shirt wearing rock stars like their too-cool-to-try-too-hard peers.

Still serving looks

Since the side-project’s demise (or not — do these performances mean there’s hope for a new abs album?[2]), Nishikawa has continued to release music, now notably, and finally, releasing under his own name. He also returned to creating novel looks and reinventing for his albums, releasing concepts like the jacket covers for UNDER:COVER 2 (itself a series of albums that musically re-envisions old hits) where he dressed in homage to various iconic female pop stars like Madonna, Amy Winehouse, and Katy Perry. Of particular note is the absence of underlying cruelty in these photos, the kind that usually accompany depictions where a man-dressed-as-a-woman is played for laughs to emphasize just how silly women are: though other photos of him do play up the hyper-feminine, commercialized form of womanhood, it comes off as sincere and fun, and, while still being used to sell a product, lacks any sort of punchline — it is presented as just another way Nishikawa wants to express himself — really, it is astounding how low these flew under the radar. Of course, with his body of work now looking like a long line of clues, this also prompted several questions by devoted fans and the general public about whether or not Nishikawa would, could, or even should confirm or deny his sexuality.

Since the side-project’s demise (or not — do these performances mean there’s hope for a new abs album?[2]), Nishikawa has continued to release music, now notably, and finally, releasing under his own name. He also returned to creating novel looks and reinventing for his albums, releasing concepts like the jacket covers for UNDER:COVER 2 (itself a series of albums that musically re-envisions old hits) where he dressed in homage to various iconic female pop stars like Madonna, Amy Winehouse, and Katy Perry. Of particular note is the absence of underlying cruelty in these photos, the kind that usually accompany depictions where a man-dressed-as-a-woman is played for laughs to emphasize just how silly women are: though other photos of him do play up the hyper-feminine, commercialized form of womanhood, it comes off as sincere and fun, and, while still being used to sell a product, lacks any sort of punchline — it is presented as just another way Nishikawa wants to express himself — really, it is astounding how low these flew under the radar. Of course, with his body of work now looking like a long line of clues, this also prompted several questions by devoted fans and the general public about whether or not Nishikawa would, could, or even should confirm or deny his sexuality.

Yet it’s not just Nishikawa — we can look at a slew of pop stars, most notably my pick for our current great male solo singer, TAEMIN, whose androgyny is part of what fuels his whole career. It is not my place or intention to speculate on the private lives of entertainers who choose to neither confirm nor deny publicly for whatever reasons, reasons they are more than entitled to, but there are undeniably a number of men and women in K- and J-pop groups who are gay, trans, queer, etc., who, as long as they continue performing their assigned roles, reap the rewards of the system, both for themselves and their entertainment companies. This is not an accusation: again, there are many reasons to side-step inquiry, among which may involve the safety of self, family and friends, reputation, and careers, and to the livelihoods of giant corporations with many employees and share-holders, that go into these decisions. This is totally beyond the scope of this essay, but it would be remiss not to acknowledge the specter that hovers over this entire essay and the East-Asian (and Western) entertainment industry.

What is apparent, however, is that Takanori Nishikawa is fearless, and that he has done valuable, innovative work for an audience of all gender and sexual orientations. In choosing to just be himself and lead with an artistic vision that often falls outside the box, both musically and visually, he has done what only few in the J-pop industry have done before him. And still Nishikawa’s work is not done, having just released his first official solo album, Singularity, which dropped last year with a Photoshop-heavy, cyborg-inspired cover. The cyborg concept seems almost redundant for him at this point, but it’s nice to see that he is still inspired and having fun, rather than letting age dictate his level of taste or willingness to continue challenging norms. Despite reinvention being a sort of harness on celebrities, and it certainly is when forced upon or unwanted, pop stars like Nishikawa seem to thrive on it, giving audiences decades of interesting, novel looks and concepts that question everything from how men and women should look and dress, to the gender binary and double standard of the idol system. As an ever-present figure and cultural mainstay, his sometimes-groundbreaking work in the industry has largely gone under the radar: ignored, dismissed, shrugged off, or treated as a passing joke. One can only hope that one day, the disservice will be corrected and Nishikawa can get his due recognition as a creative artist, just like his biggest influence, Prince. Thirty years into his career, he might just be as omnipresent, and forgettable, as bands like Southern All Stars or Mr. Children, but it’s important not to take for granted, or forget, trailblazing icons like Takanori Nishikawa.

1 After decades of seeing (and admittedly, using) the phrase “all-girl band” as a reference to the “all-male band” as default, I just love when I get to use the phrase all-male band instead.

2 abingdon boys school is the one project of his that I wish we would see more of — there was just something about those particular four guys in a room that seemed to bring out the magical, musical alchemy of J-rock, both visually and aurally, that for a brief moment in time, re-framed both the genre and Nishikawa’s career; abs3, please.

[ All images original scans, except for those credited to here, here, here, and here. ]

That last point is a stretch, and none of the artists briefly profiled could be considered to have gained “mainstream” success (Rappers Novelist and Kodak Black, piano prodigy Joey Alexander, popster Låpsley, etc.), but the New Yorker wouldn’t be the New Yorker if it didn’t purport to being on the absolute up-and-up. As in TIME‘s special Fall 2001 issue, which featured Hikaru Utada, (notably, she was working on her American debut with Foxy Brown and the Neptunes and planning to retire very young, around 28, probably to become a neuroscientist), articles like these tend to be peak Western exposure for said artists, rather than the beginning of a phenomenon, though BABYMETAL does get relatively considerable space. Writes Trammell,

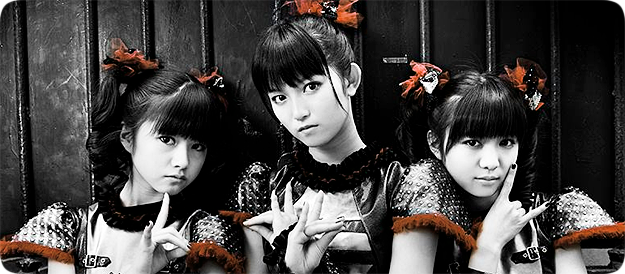

That last point is a stretch, and none of the artists briefly profiled could be considered to have gained “mainstream” success (Rappers Novelist and Kodak Black, piano prodigy Joey Alexander, popster Låpsley, etc.), but the New Yorker wouldn’t be the New Yorker if it didn’t purport to being on the absolute up-and-up. As in TIME‘s special Fall 2001 issue, which featured Hikaru Utada, (notably, she was working on her American debut with Foxy Brown and the Neptunes and planning to retire very young, around 28, probably to become a neuroscientist), articles like these tend to be peak Western exposure for said artists, rather than the beginning of a phenomenon, though BABYMETAL does get relatively considerable space. Writes Trammell, In many ways this is a sign of the outrageous gender binaries that comprise the marketing and distribution of Japanese idols; for purposes of the music itself, it also reinforces the notion that genres that comprise huge male audiences (hard rock, metal) can be deemed authentic and worthy of critical attention, while those that women enjoy are considered fluff that no one would ever take seriously. Under that idea, it’s hardly surprising that a group like BABYMETAL could make it in the circles of certain American subcultures, and less so that articles in the Western media feel the need to justify their interest in the group by constantly reminding readers that their material was written by veterans of the metal genre (Nobuki Narasaki, Herman Li, Sam Totman, Takeshi Ueda, etc.), or that the girls themselves are influenced, or appreciated by,

In many ways this is a sign of the outrageous gender binaries that comprise the marketing and distribution of Japanese idols; for purposes of the music itself, it also reinforces the notion that genres that comprise huge male audiences (hard rock, metal) can be deemed authentic and worthy of critical attention, while those that women enjoy are considered fluff that no one would ever take seriously. Under that idea, it’s hardly surprising that a group like BABYMETAL could make it in the circles of certain American subcultures, and less so that articles in the Western media feel the need to justify their interest in the group by constantly reminding readers that their material was written by veterans of the metal genre (Nobuki Narasaki, Herman Li, Sam Totman, Takeshi Ueda, etc.), or that the girls themselves are influenced, or appreciated by,  While Marty Friedman believed that Japanese pop music would only reach an audience outside Japan “with luck” and “timing,” and other factors that couldn’t be planned, BABYMETAL, has been a slow, methodical climb to relevance, not least of which included shows in Paris, New York, and the UK, and opening for Lady Gaga’s ArtRave: The Artpop Ball tour starting back in 2014.

While Marty Friedman believed that Japanese pop music would only reach an audience outside Japan “with luck” and “timing,” and other factors that couldn’t be planned, BABYMETAL, has been a slow, methodical climb to relevance, not least of which included shows in Paris, New York, and the UK, and opening for Lady Gaga’s ArtRave: The Artpop Ball tour starting back in 2014.  That being said, in rare cases the music can transcend context, as BABYMETAL’s fantastic new album, METAL RESISTANCE, does. There are some truly epic and astounding risks the album takes and pulls off, particularly with lead tracks “

That being said, in rare cases the music can transcend context, as BABYMETAL’s fantastic new album, METAL RESISTANCE, does. There are some truly epic and astounding risks the album takes and pulls off, particularly with lead tracks “

In their place are groups like PASSPO☆, whose shtick is travel in general and flight attendants in particular. In addition to the costumes and lyrical content, the group has also invented a dubious vocabulary to make them stand out from groups with other,

In their place are groups like PASSPO☆, whose shtick is travel in general and flight attendants in particular. In addition to the costumes and lyrical content, the group has also invented a dubious vocabulary to make them stand out from groups with other,  Of course, groups rocking a large number of members is nothing new. AKB48 had a predecessor in similar idol groups like Onyanko Club and Bishoujo Club 31. Momoiro Clover Z owe a debt to a rarer kind of ancestor like SAINT FOUR. That short-lived idol group churned out

Of course, groups rocking a large number of members is nothing new. AKB48 had a predecessor in similar idol groups like Onyanko Club and Bishoujo Club 31. Momoiro Clover Z owe a debt to a rarer kind of ancestor like SAINT FOUR. That short-lived idol group churned out  The

The  I’ve spoken about the

I’ve spoken about the

As

As

The sociological notion of the individual versus the collective isn’t a very far-fetched schema to apply to

The sociological notion of the individual versus the collective isn’t a very far-fetched schema to apply to  Even Mimi, a lackadaisical love interest, moves from worshiping Sang-Gyu (“I thought of you always, and singing [after] records while others were slacking off. So…so you are… You are ‘soul’ to me”) to finding her inner diva, perhaps the film’s most blatant symbolic representation of discovering one’s own rhythm. Her transformation from band maid to band mascot seems a bit damning at first in its depiction of females finding “freedom” through mini-skirts and make-up, but the confidence and control with which Mimi eventually works the audience shows neither sexual pandering nor demented irony; Mimi finds expression through movement, vocals, and female solidarity, abandoning Sang-Gyu’s flippant affection and embarking on a much more reliable love affair with music.

Even Mimi, a lackadaisical love interest, moves from worshiping Sang-Gyu (“I thought of you always, and singing [after] records while others were slacking off. So…so you are… You are ‘soul’ to me”) to finding her inner diva, perhaps the film’s most blatant symbolic representation of discovering one’s own rhythm. Her transformation from band maid to band mascot seems a bit damning at first in its depiction of females finding “freedom” through mini-skirts and make-up, but the confidence and control with which Mimi eventually works the audience shows neither sexual pandering nor demented irony; Mimi finds expression through movement, vocals, and female solidarity, abandoning Sang-Gyu’s flippant affection and embarking on a much more reliable love affair with music.

But we take these things for granted now, almost as much as all those tough looking guys on the boy band side like Tohoshinki/DBSK who have to consciously navigate the tender line between innocence and sexual development in order to appeal to young girls who should not, should never, think about sex. The angry young man archetype has been replaced by the new Asian boy band archetype: the angry young dancing man, who wraps himself in Johnny Cash’s wardrobe, loves to chill with the boys, and sings about how hard it is to just like, live your own life, man. As it is the girl groups’ duty to “

But we take these things for granted now, almost as much as all those tough looking guys on the boy band side like Tohoshinki/DBSK who have to consciously navigate the tender line between innocence and sexual development in order to appeal to young girls who should not, should never, think about sex. The angry young man archetype has been replaced by the new Asian boy band archetype: the angry young dancing man, who wraps himself in Johnny Cash’s wardrobe, loves to chill with the boys, and sings about how hard it is to just like, live your own life, man. As it is the girl groups’ duty to “